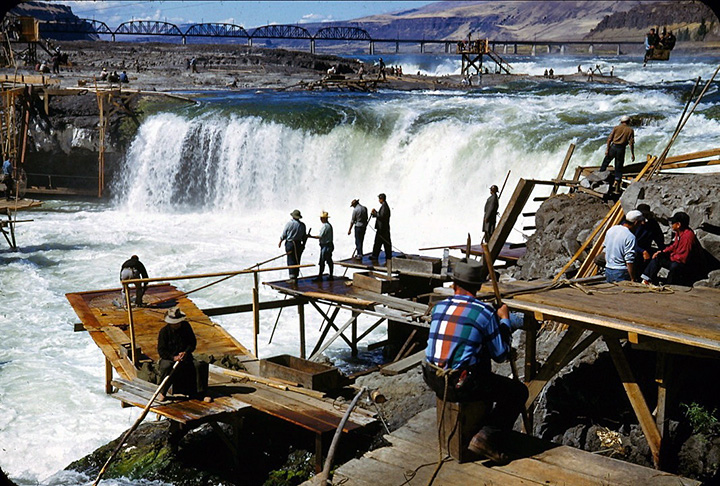

At that point of realization, we may confront the question: Has my grief over such immense damage and loss, and dread over our future suffering—has it now become a pressure on my family and local community? In 1947, when I was ten, our family took a road trip from Chicago to LA. Coming across Idaho’s panhandle, we dropped down to follow the Columbia, and stopped at a place on the river just inside Oregon. I got out of the car and walked toward the river. There, young and middler men crouched and knelt far out on rickety platforms, poised with spears, plunging and drawing them up, salmon writhing, all suspended precariously over the surging river, white water falling over and roiling around great rocks, girls taking the salmon from the spear-fishers, carrying them, some still wriggling, up the shore to their mothers, aunts and older sisters, who were cleaning and storing the finally-still fish: it was a scene beyond my world, strange but stunning, holding me then, and since.

In early 1994, shortly after Carole and I moved to Portland, we drove through the Columbia Gorge to find this place, Celilo, almost fifty years later. At the spot on the map, we stopped and walked toward the great river. Again I was stunned, for now the river was untroubled and smooth, of course, without platforms, empty of people and their work. There were a few fragile shacks up the shore, on the other side of the Union Pacific tracks. But at the river’s edge, there was only a small metal page of words, telling tourists that this was the place named Celilo, now covered and smoothed over by the water held back by the dam at the Dalles. Nothing really to tell us of the great seasonal dramas here, going back several thousand years, where the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest gathered to trade their news and goods, to fish, and to conduct their ceremonies of gratitude for creation. Almost no sign at alI, except for this piece of metal and the memories of the people here then and now, and deeply placed within this once small boy now grown, unable to speak, flooded by grief for the loss, especially to the remaining tribal people, but to us all, I feel—the loss that I would say now is both social and natural, the energy and tenderness of a sacred blanket holding people, nature’s place and meaning together, sundered in the early 1950s, yet still that blanket and its people, fish, river itself, and Earth—all are remembering and weeping here.

At that point of realization, we may confront the question: Has my grief over such immense damage and loss, and dread over our future suffering—has it now become a pressure on my family and local community? |

But because of our relational work, we can ask the leaders of our local communities to look at these questions with us; we can raise all of this within our own families—and let the fur fly, perhaps learning with both sides of our brains that awakening is full of suffering, promise, and healing.

We may find that our local communities can use the relational organizing process to better understand these larger questions, and understand them among people we have come to know and trust. For Earth’s crisis, in climate and species-loss, has local expressions, everywhere. Those local expressions become serious pressures on our families and local communities. They are serious threats: —to human health, from diseases ranging from asthma and allergies, to heart disease, to mental imbalances; —to water supply and quality; —to air quality and temperature; —to ruined soil and costly, unsafe food; —to forests, homes and communities, from fires, floods, slides and sprawl; —to local and regional economies from the resulting chaos; —to viable, even survivable futures for our children, grandchildren and great- grandchildren. These local expressions can be “broken down” into issuable, organizable components.

And we can take the same approach to engage the enormous opportunity here, in the Great Work of creating Earth-supporting local economic enterprises, saying yes to Creation. High-quality relational organizing can give us the confidence, skill-set and lens to conduct real conversations with each other about what I’ve called the YES/NO/YES of our situation—including our massive layers of denial, and ways through them. From these conversations, we can create appropriate public expressions of lament over what the system-story of our political economy, with our complicity, has done to nature, and hence to ourselves—and over what we will continue to lose. |